New World screwworms are moving closer to the U.S. border, threatening the health of horses and livestock. Learn about the risks, USDA response, and how to protect your animals.

The New World screwworm (NWS), a parasitic fly once eradicated from the United States in the 1980s, has been detected just 70 miles south of the U.S.-Mexico border in Nuevo León, Mexico. This alarming development marks the northernmost detection of the pest during its recent resurgence, according to Mexico’s National Service of Agro-Alimentary Health, Safety, and Quality (SENASICA) and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA)1.

Table of contents [Show]

A Growing Threat to Horses and Livestock

The New World screwworm is infamous for its flesh-eating larvae, which feed on living tissue in open wounds. Female flies lay eggs on the edges of wounds, and within hours, the larvae begin burrowing into the flesh. If left untreated, infestations can lead to severe infections and even death. While the pest primarily affects horses and livestock, it can also harm wildlife and, in rare cases, humans.

The latest case involved an 8-month-old cow transported from southern Mexico to a feedlot in Nuevo León. This highlights the role of livestock movement in the pest's spread. SENASICA has reported over 5,000 cases of screwworm infestations in animals this year, with the majority found in cattle, but also in horses, dogs, and sheep.

U.S. Response and Preparedness

In response to the growing threat, the USDA has ramped up surveillance along the southern border, deploying nearly 8,000 traps across Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico. To date, over 13,000 samples have been screened, with no NWS flies detected in the U.S. However, officials remain on high alert and are prepared to release sterile flies in affected areas to curb the pest's spread1.

The USDA has also closed ports to cattle, bison, and horse imports from Mexico since July, following earlier detections farther south. Additionally, the agency is investing in sterile fly production facilities in Texas, with plans to release up to 300 million sterile flies per week once the facilities are operational.

"This parasite doesn’t discriminate," said Dr. T.R. Lansford, Texas assistant state veterinarian. "It affects all warm-blooded animals, making vigilance our best line of defense".

Implications for U.S. Horses and Livestock

The screwworm's northward migration poses a significant threat to the U.S. horse and livestock industries, which are vital to the nation’s agricultural economy. The USDA has emphasized the importance of early detection and reporting, urging horse and livestock owners and veterinarians to monitor animals for unusual wounds or signs of larvae.

"This is a critical and urgent threat to America’s cattle producers," said Colin Woodall, CEO of the National Cattlemen’s Beef Association. "The speed at which screwworm has moved through Mexico is a stark reminder of the need for vigilance and action".

What You Can Do

Veterinarians and horse and livestock owners, especially those near the southern border, are encouraged to inspect animals regularly for signs of screwworm infestation. Look for draining or enlarging wounds, discomfort, or visible larvae. If you suspect an infestation, contact your state animal health official or USDA area veterinarian immediately.

The USDA is also working closely with Mexican authorities to bolster eradication efforts and prevent further spread. "American ranchers and families should know that we will not rely on Mexico to defend our industry, our food supply, or our way of life," said U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke Rollins.

Screwworms and Bot Fly Larvae: How to Tell the Difference

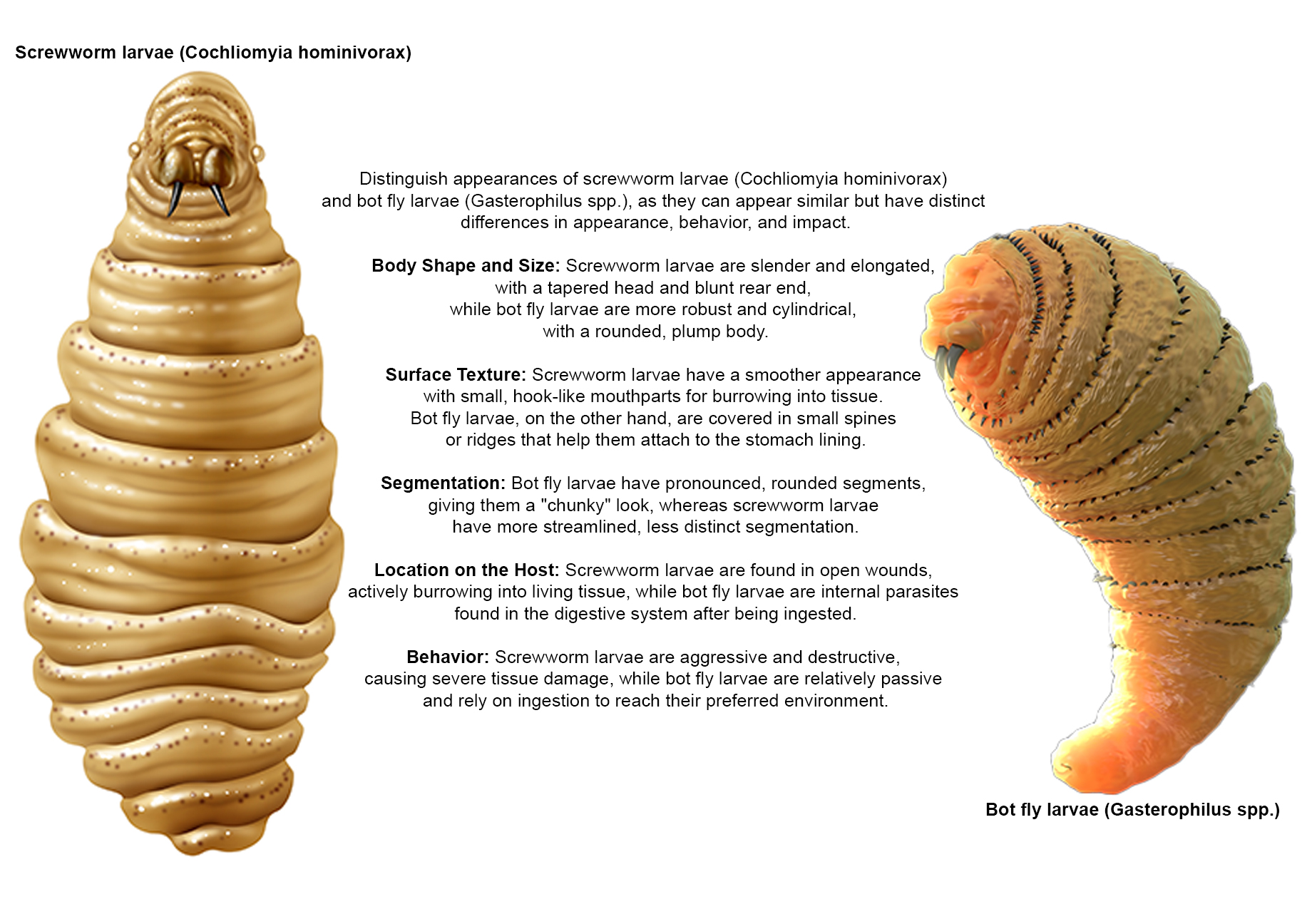

Screwworm larvae (Cochliomyia hominivorax) and bot fly larvae (Gasterophilus spp.) may look similar, but there are distinct differences that horse owners should know to identify and address infestations accurately.

- Body Shape and Size: Screwworm larvae are slender and elongated, with a tapered head and blunt rear end, while bot fly larvae are more robust and cylindrical, with a rounded, plump body.

- Surface Texture: Screwworm larvae have a smoother appearance with small, hook-like mouthparts for burrowing into tissue. Bot fly larvae, on the other hand, are covered in small spines or ridges that help them attach to the stomach lining.

- Segmentation: Bot fly larvae have pronounced, rounded segments, giving them a "chunky" look, whereas screwworm larvae have more streamlined, less distinct segmentation.

- Location on the Host: Screwworm larvae are found in open wounds, actively burrowing into living tissue, while bot fly larvae are internal parasites found in the digestive system after being ingested.

- Behavior: Screwworm larvae are aggressive and destructive, causing severe tissue damage, while bot fly larvae are relatively passive and rely on ingestion to reach their preferred environment.

Understanding these differences is crucial for horse owners to take appropriate action. Screwworm infestations require urgent veterinary intervention, while bot fly infestations can often be managed with regular deworming and grooming to remove eggs before they are ingested.

A Long Road Ahead

While the USDA’s efforts are robust, experts warn that eradicating the screwworm will take years of sustained work. "In terms of the fly life cycle and the scale of what’s needed, we’re probably looking at close to a decade of sustained work," said Dr. Lansford.

For now, vigilance and early action remain the best tools to protect U.S. horses and livestock and prevent the screwworm from re-establishing itself in the country.